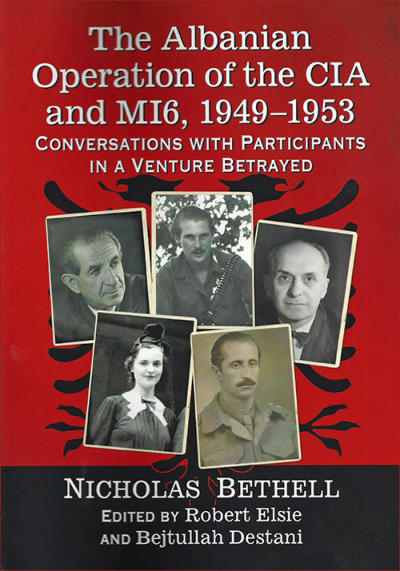

Nicholas Bethell

The Albanian Operation of the CIA

and MI6, 1949-1953

Conversations with Participants in a Venture Betrayed

Edited by Robert Elsie and Bejtullah Destani

ISBN 978-1476663791 McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina 2016 187 pp.Introduction

Kim Philby (1912-1988), a high-ranking British intelligence officer and, at the same time, a spy for the Soviet Union, is one of the most fascinating figures in the murky history of twentieth-century espionage. He was at war with the British establishment, of which he was himself an integral part. Among his victims, in very concrete terms, were hundreds of Albanians. This book provides insight into the so- called Albanian Operation carried out by the British and American secret services in the years 1949-1953 to infiltrate communist Albania and topple the hermetic Stalinist regime that had seized power there. It focuses on conversations and interviews with the people who actually took part in the Operation in one way or another: British and American officials, and Albanian fighters who infiltrated Albania and escaped alive.The Historical Background

Albania, a small country in southeastern Europe, had gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1912. In 1939, the realm of King Zog, its autocratic ruler, was invaded by Italian forces. The Albanian king fled abroad and the country became part of Mussolini's new Roman Empire. With the capitulation of Fascist Italy on 8 September 1943, Nazi Germany occupied Albania to ensure that the country did not fall into the hands of the British. Throughout the period of Italian and German occupation, the Albanians were very divided in their loyalties. Many thought it best to submit and adapt to the new situation, other called for armed resistance. Even within the resistance, there was deep division, with the presence of three rival resistance groups: the communist partisans under Enver Hoxha (1908-1985) and Mehmet Shehu (1913-1981), the anticommunist Balli Kombëtar (National Front) under Midhat bey Frashëri (1880-1949), and the smaller royalist Legaliteti (Legality) movement under Abas Kupi (1892-1976). The German Foreign Office endeavoured to revive an independent Albanian state to safeguard German strategic interests in the Balkans. A new administration was formed in Tirana, but it was not able to exert much authority over the country, which was now enmeshed in a bloody civil war. When German troops withdrew from Albania at the end of November 1944, the communists under Enver Hoxha took power and subsequently set up the People’s Republic of Albania. Once in office, the new regime took immediate measures to consolidate its power. In January 1945, a special people’s court was set up in Tirana under Koçi Xoxe (1917-1949), the new minister of the interior from Korça, for the purpose of trying “major war criminals.” This tribunal conducted a series of show trials which went on for months, during which hundreds of actual or suspected opponents of the regime were sentenced to death or to long years of imprisonment. In March, private property and wealth were confiscated by means of a special profit tax, thus eliminating the middle class, and industry was nationalized. In August 1945, a radical agrarian reform was introduced, virtually wiping out the landowning class which had ruled the country since independence in 1912. At the same time, initial efforts were undertaken to combat illiteracy, which cast its shadow over about 80 percent of the population. Apart from a shattered economy and anticommunist uprisings in the north of the country, the new regime had a number of major foreign policy problems to deal with. Greece still considered itself in a state of war with Albania, relations with the United States had declined dramatically, and ties with the United Kingdom were severely strained after the so-called Corfu Channel incident of 22 October 1946, in which two British destroyers hit mines off the Albanian coast. The communist leadership in Albania, always plagued by factional division, had split into two camps shortly after it took power. One side, represented by poet Sejfullah Malëshova (1901-1971), in charge of cultural affairs, contended that Albania should conduct an independent foreign policy, maintaining relations with both East and West, and more moderate domestic policies to encourage national reconciliation. The pro-Yugoslav faction, led by minister of the interior Koçi Xoxe, advocated closer ties with Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, and insisted that more radical social and economic policies be introduced and coordinated with those being implemented by Belgrade. Xoxe and his Yugoslav advisors won out, and in February 1946, Malëshova was expelled from the Politburo and condemned as a “right-wing opportunist.” Enver Hoxha himself seems to have maintained a tactically vague position, lying low and waiting for a chance to eliminate his opponents for good. Relations with the United Kingdom and the United States worsened, and in July 1946, Enver Hoxha signed a treaty of friendship, cooperation and mutual assistance with Yugoslavia following a visit to Belgrade. This was envisaged as the first step towards the union of the two countries and Albania was to remain a virtual Yugoslav colony until June 1948. During this period, Koçi Xoxe, as minister of the interior, made ample use of his powers over the security apparatus and police to eliminate all potential rivals and enemies. These witch hunts, known euphemistically in official party history as the period of Koçi-Xoxism, resulted in the execution or imprisonment not only of political figures but also of numerous talented writers and intellectuals. The rift between Tito and Joseph Stalin in 1948 gave Enver Hoxha a Soviet ally with whose support he could now act to preserve his own position, and he soon managed to eliminate his rivals. Albania became the first Eastern European country to denounce Yugoslavia after the latter’s expulsion from the Cominform, i.e., the Soviet bloc, on 17 June 1948, and all Yugoslav advisors were expelled from the country without delay. Albania had entered the Soviet fold. The series of show trials and purges which ensued were similar to those that took place elsewhere in Eastern Europe in the late 1940s and early 1950s. At its first congress of 8-22 November 1948, the purged Albanian Communist Party was renamed the Albanian Party of Labour. Koçi Xoxe’s own reign of terror came to an end when he was convicted of treason in May 1949 and executed on 11 June of that year. For the people of Albania, the late 1940s was a period of blatant terror. Even those who had supported the communists in 1944 realised that the ideals of socialism and equality had become a farce. Nowhere in the eastern bloc were people more oppressed, more terrified into submission than in Albania. Albania’s alliance with the Soviet Union had several advantages. The Soviets offered much food and economic assistance to replace the losses caused by the interruption of Yugoslav aid. They also gave the Hoxha regime military protection both from neighbouring Yugoslavia and from the West at a time when the Cold War was at its height. By 1947, the Western world and the Soviet Union, one-time allies against Nazi Germany, were embittered rivals in a Cold War that was played out in the Balkans primarily in Greece. The Powers had divided the spoils of Europe in advance during the war. The major Balkan countries: Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Romania, were to go to the Soviet bloc whereas Greece was to be part of the West. No specific provision was made for Albania. Greece, however, descended into a bloody civil war between the Greek Communist Party, supported by the Soviet Union and the communist countries of the Balkans, and anti-communist government forces, supported by Britain and the United States.The Albanian Operation

The post-war Albanian Operation was one of the first Western attempts to subvert a country behind the Iron Curtain. It was devised initially around 1946 by officials of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) who believed, rather naively, that if they could parachute a few well-trained agents into Albania, they could bring about a mass uprising against the communist regime. By 1949 the CIA was heavily involved in the project, too. The British liaison officer for the project in Washington was none other than Kim Philby. The venture was facilitated by the large numbers of Albanian refugees languishing in camps in Italy and Greece. When contacted, with the intercession of their exile leaders, they were more than willing to be recruited. The volunteers were given brief and vastly insufficient training, primarily in Malta and southern Germany, and were sent into Albania by boat, overland from Greece, and by parachute drop, in small groups, mainly from the second half of 1949 to Easter 1952. Most of them were captured and shot the moment they arrived. The communist security forces had seemingly been informed in advance of their arrival. The Albanian fighters had thus been betrayed. In all, about 300 agents and civilians are thought to have been killed in the operation. This is probably a conservative estimate. It has been suggested that the Albanian Operation, promoted by Britain and later by the United States, was intended not so much to overthrow the Hoxha regime, but to weaken communist forces fighting in Greece. If this is true, the Albanian fighters who returned to liberate their country and perished in doing so, were betrayed twice over. They were mere pawns in a larger game. The Albanian Operation was eventually abandoned and hushed up. For Britain and the United States, it was a humiliating disaster about which they did not want the world to know, in particular because they still did not understand the exact reason for its failure. It was only years later, with the defection of Kim Philby to Moscow, that the full extent of his treachery became apparent. The full story of the disastrous Albanian Operation was first pieced together by Nicholas Bethell in his book The Great Betrayal: The Untold Story of Kim Philby's Biggest Coup, published in London in 1984. Lord Bethell based his book on conversations and interviews recorded with those involved in the project at the time, among them being some of the Albanian fighters who survived and managed to escape from Albania. The interviews, which were conducted over a three-year period from May 1981 to August 1984, were not themselves published at the time. It was Lord Bethell's wish to edit them and make them available to the public domain. However, suffering from Parkinson's disease in later life, he passed away before he could realise this intention. We are grateful to the Bethell family for providing this first-hand material to the Centre for Albanian Studies in London for publication. The present edition of the conversations and interviews on a venture betrayed will, we hope, throw new light on what actually took place. Robert Elsie Berlin, Germany Buy this Book on AMAZON

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |