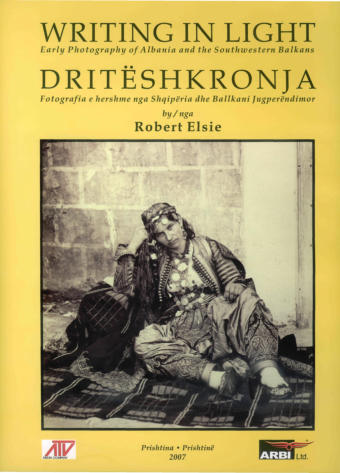

Writing in Light

Early Photography of Albania and the Southwestern Balkans

Dritëshkronja

Fotografia e hershme nga Shqipëria dhe Ballkani

ISBN 978-9951-8735-1-2 ATV Media Company & Arbi Ltd, Prishtina 2007 311 pp. PREFACE Dritëshkronja is a curious term in Albanian. It means "writing in light" and was invented in the nineteenth century to serve as the Albanian word for photography. The term soon became obsolete and was replaced by the international word fotografia. We have given prominence to the old word here to illuminate something of early photography in nineteenth and early twentieth-century Albania, that once wild and savage land in southeastern Europe. The history of photography in Albania and the southwestern Balkans begins around the time of Josef Székely (1838-1901). This young Viennese photographer was appointed by the Balkan Commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences to take part in an expedition to Albania in 1863 with scholar Johann Georg von Hahn (1811-1869). The fifty photographs that resulted from the exploration of the Drin valley are among the earliest ever taken in Albania, Kosova and Macedonia, and are being presented here for the first time. Josef Székely would have been surprised to discover that the town of Shkodra or Scutari, from which they set off, already possessed a noted local photographer in the person of Pietro Marubbi or Marubi (1834-1903). We have alas no indication of whether the two men met during Székely's brief visit. Pietro Marubbi was an Italian painter and photographer who, as a supporter of Garibaldi, had emigrated from Piacenza, Italy, to Shkodra for political reasons around the year 1850. Here, he founded a photo business, Foto Marubi, with cameras he had brought with him. The oldest photos in the collection date from 1858-1859, just before those of Székely. Some of them were published in The London Illustrated News, the La Guerra d'Oriente and L'Illustration. Marubi was assisted by the young Rrok Kodheli (1862-1881) and his brother, Kel Kodheli (1870-1940), the latter of whom took over the family business after Pietro's death and changed his name to Kel Marubi. He furthered techniques with special effects and learned to retouch the negatives. He also began photographing outside the studio with more advanced cameras. Closely related to the Marubis was the photographer and painter, Kolë Idromeno (1860- 1939), of Shkodra. In 1883, he opened a photo studio with cameras imported from the Pathé Company in France and in 1912, he became the first person in Albania to import moving picture equipment and to show films. Indeed, in August of that year, he signed a contract with the Josef Stauber Company in Austria to set up the country's first, rudimentary public cinema. The third generation of Marubi photographers in the family was Kel's son, Gegë Marubi (1907 1984). He studied in Lyon in 1923-1927 at the first school of photography and cinema, founded by the Lumière brothers, and worked in Shkodra as a professional photographer from 1928 to 1940. Gegë Marubi pioneered working with celluloid instead of glass plates. The Marubi Photo Collection (Fototeka Marubi) in Shkodra comprises over 150,000 photos, many of which are of great historical, artistic and cultural significance. The collection captures and documents northern Albanian history from the League of Prizren onwards. It contains fascinating photographs of tribal leaders, highland uprisings, town life in Shkodra and various public events. Two albums of the Marubi photos have been published (Paris 1995 and Rome 2004). Attempts have been underway since 1994, with UNESCO funding, to preserve the collection and make it available. The other great name in Balkan photography and cinematography is that of the Manakis brothers in Macedonia. Yannaki Manakis (1878-1954) and his brother, Milton Manakis (1882- 1964), were born in Avdela near Grevena - now in northern Greece - and were of Aromanian (Vlach) origin. From 1898 to 1904 they owned a photo shop in Janina (Ioannina), and in 1905 they moved to Monastir (Manastir/Bitola) - now in the Republic of Macedonia - where they opened a Studio for Art Photography. Yannaki and Milton Manakis took more than 17,300 photographs in 120 localities. In 1905, they also made the first moving pictures in the Balkans. This album is, however, not concerned with native Albanian and Balkan photography, but rather with foreign collections that have remained unpublished or little known up to the present, and that throw much light on Albania and the southwestern Balkans at the time. The first of these is the said collection of Josef Székely, dating from 1863 and consisting of fifty spectacular photos, including views of Shkodra, Prizren, Ohrid and Monastir. By the end of the nineteenth century and in the early decades of the twentieth, it was by no means a rarity for foreign scholars, writers and adventurers travelling in the wilds of Albania to take cameras with them and to record what they saw. Much of their material, not always photos of high quality, served to illustrate their book publications on Albania. Two of the most distinguished scholars in the field of Albanian studies, both Austro- Hungarians, have left us photo collections which have escaped public attention until recently. They are Baron Franz Nopcsa (1877-1933) who, with his Albanian secretary and co- photographer Bajazid Elmaz Doda (ca. 1888-1933), lived in Shkodra for a number of years at the beginning of the twentieth century and travelled through those isolated mountain reaches as few others had done at the time, and Maximilian Lambertz (1882-1963) who visited Albania as part of another scholarly expedition organized by the Balkan Commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. These photographs from the first two decades of the twentieth century form the second section of this album. Others travellers in the southern Balkans photographed what they saw and experienced, but never conceived of the scholarly value their photos would later have. Such was the case of the Dutch officers sent to Albania in 1913-1914 to set up the gendarmerie of the newly created Albanian State. Each was seconded to the Balkans not only with his normal military equipment, but also - to our good fortune - with a camera. The men recorded what they saw and experienced at a defining moment in Albanian history: the nation's late independence after five hundred years of Ottoman rule, the arrival of a new German sovereign, Prince Wilhelm zu Wied, to reign over his tiny Balkan kingdom, and the country's descent into chaos precipitated by domestic strife, the Balkan Wars and the outbreak of World War I. Their pictures were preserved by the officers' descendants in Holland. Most of them have never been seen by the general public before. The author wishes to express his gratitude to the institutions preserving the original photos and prints for their generous co-operation. The Photo Archives of the Austrian National Library in Vienna (Bildarchiv, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien) stores the Székely collection under the inventory number VUES IV 41.055-41.104, the Lambertz collection under Pk 4948, Pk 4950 and Pk 4951, and the photos taken by Bajazid Elmaz Doda under NB902060B to NB902076B. The Nopcsa collection, for its part, is preserved in the Hungarian Natural History Museum (Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum) in Budapest. Most of the photo material from the Dutch Military Mission was discovered in copies at the Netherlands Institute of Military History (Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie) in The Hague. Our thanks also go the many people who have helped make this book possible, among them: Durim Bani (The Hague), Jolien Berendsen-Prins of the Thomson Foundation (Groningen), Kastriot Dervishi (Tirana), Okke Groot of the Netherlands Institute of Military History (The Hague), Matthias Hofmann (Halle), Gerda Mulder of the Nederlands Fotomuseum (Rotterdam), Uwe Schögl, deputy director of the Photo Archives of the Austrian National Library (Vienna), Harrie Teunissen (Leiden) and Richard van den Brink (Utrecht). It remains for me to hope that the present album, containing an astounding wealth of unknown photographic material about a region which, at the time, was the least known corner of Europe - and has perhaps remained so - will provide much insight and enjoyment. Robert Elsie The Hague, Holland summer 2007 PARATHËNIE Dritëshkronja, kjo fjalë e bukur shqipe u përdor për herë të parë në shekullin e nëntëmbëdhjetë. Me kalimin e kohës ajo u zëvendësua me fjalën ndërkombëtare fotografia. Këtu po e ringjallim një herë për të krijuar një lidhje midis fotografisë së hershme dhe Shqipërisë së shekullit të nëntëmbëdhjetë dhe të fillimit të shekullit të njëzetë. Historia e fotografisë në Shqipëri dhe në jugperëndim të Ballkanit filloi rreth kohës së Jozef Sekelit (1838-1901). Komisioni për Ballkanin i Akademisë së Shkencave të Austrisë e caktoi fotografin e ri vjenez që të merrte pjesë në një udhëtim në Shqipëri në vitin 1863, një ekspeditë e drejtuar nga albanologu Johan Georg fon Han (1811-1869). Pesëdhjetë fotografitë të cilat rezultuan nga udhëtimi nëpër viset e Drinit dhe të Vardarit janë ndër më të hershmet në Shqipëri, në Kosovë dhe në Maqedoni. Jozef Sekeli do të ishte i habitur, po të kishte ditur se në qytetin e Shkodrës, nga janë nisur, ishte një fotograf vendas, me emrin Pietro Marubbi, shqip Pjetër Marubi (1834-1903). Për fat të keq nuk dimë nëse të dy fotografët janë takuar gjatë qëndrimit të Sekelit në Shkodër. Marubi, një piktor dhe fotograf italian, si përkrahës e Garibaldit, u detyrua të ikte nga Piaçenca të Italisë për arsye politike dhe gjeti strehim në Shkodër rreth vitit 1850. Këtu themeloi dyqanin Foto Marubi me disa aparate fotografike që i kishte sjellë me vete. Fotografitë më të vjetra të koleksionit janë nga vitet 1858-1859, pak kohë para Sekelit. Disa foto të Marubit u botuan në revistat "The London Illustrated News," "La Guerra d'Oriente" dhe "L'Illustration." Marubi kishte si ndihmës djaloshin Rrok Kodheli (1862-1881) dhe vëllanë e tij, Kel Kodheli (1870-1940). Më vonë, pas vdekjes së Pjetrit, Kel Kodheli e trashegoi firmën familjare dhe mori emrin Kel Marubi. Keli mësoi të përdorte efekte të posaçme dhe të përpunonte negativat. Gjithashtu ai filloi të fotografonte jashtë studios me aparate më moderne. Lidhur ngushtë me familjen Marubi ishte fotografi dhe piktori Kolë Idromeno (1860-1939) i Shkodrës. Në vitin 1883, Idromeno hapi një fotostudio me aparate fotografike të marra nga firma Pathé në Francë, dhe në vitin 1912, importoi për herë të parë në Shqipëri aparate filmike dhe shfaqi filma. Në gusht të atij viti, firmosi një kontratë me firmën Josef Strauber në Austri për të krijuar atë që mund të quhet kinemaja e parë në Shqipëri. Brezi i tretë i fotografëve Marubi ishte djali i Kelit, Gegë Marubi (1907-1984). Ai studioi në Lion të Francës në 1923-1927 në shkollën e parë të fotografisë dhe të kinemasë të themeluar nga vëllezërit Lymier, dhe punoi në Shkodër si fotograf nga viti 1928-1940. Ishte i pari në familje që përdori celuloid në vend të pllakave prej xhami. Fototeka Marubi përfshin dhe dokumenton historinë e Shqipërisë së Veriut që prej Lidhjes së Prizrenit e më tej. Përfshin fotografi të mahnitshme të udhëheqësve të fiseve të veriut, të kryengritjeve të malësorëve, të jetës qytetare në Shkodër dhe të ngjarjeve të ndryshme publike. Vetëm pak fotografi të Marubit janë botuar deri tani (Paris 1995 dhe Romë 2004). Që prej vitit 1994, me mbështetjen e UNESCO-s, bëhen përpjekje për ruajtjen e koleksionit dhe për publikimin e tij. Koleksioni tjetër i njohur i fotografisë dhe të kinematografisë ballkanike ështe ai i vëllezërve Manakis në Maqedoni. Janaki Manakis (1878-1954) dhe vëllai Milton Manakis (1882-1964) lindën në fshatin Avdela afër Grevenës, tani në veri të Greqisë, dhe ishin me prejardhje vllahe (aromune). Nga 1898-1904 kishin një dyqan fotografik në Janinë dhe në vitin 1905 u vendosën në Manastir, tani në Republikën e Maqedonisë, ku hapën Studion për Artin Fotografik. Janaki dhe Milton Manakis bënë më shumë se 17.300 fotografi në 120 vende të ndryshme. Në vitin 1905 realizuan edhe filmin e parë në Ballkan. Mirëpo, ky album nuk i kushtohet fotografisë shqiptare vendase por koleksioneve të huaja të cilat kanë mbetur të pabotuara apo pak të njohura deri tani dhe të cilat hedhin dritë mbi Shqipërinë dhe Ballkanin jugperëndimor të kohës. Koleksioni më i hershëm i huaj është pikërisht ai i Jozef Sekelit, prej vitit 1863, i cili përbëhet prej pesëdhjetë fotografive të mahnitshme, duke përfshirë pamje të Shkodrës, të Prizrenit, të Ohrit dhe të Manastirit. Në fund të shekullit të nëntëmbëdhjetë dhe në fillim të shekullit të njëzetë, nuk ishte më dukuri e rrallë për shkencëtarë, shkrimtarë dhe aventurierë në malet e egra të Shqipërisë që ata të merrnin me vetë një aparat fotografik. Disa prej fotografive të tyre u botuan nëpër librat dhe gazetat e kohës. Dy nga shkencëtarët më të spikatur në fushën e albanologjisë së kohës na lanë koleksione të fotografive të panjohura deri para pak kohe. I pari është baroni hungarez Franc Nopça (1877- 1933) i cili, bashkë me sekretarin e bashkëfotografin e tij shqiptar Bajazid Elmaz Doda (rreth 1888-1933), jetoi në Shkodër për disa vjet në fillim të shekullit të njëzetë dhe udhëtoi shumë në Malësinë e Madhe, gjë e rrallë për një të huaj në atë kohë. I dyti është austriaku Maksimilian Lamberc (1882-1963), i cili vizitoi Shqipërinë gjatë Luftës së Parë Botërore në kuadrin e një ekspedite shkencore të organizuar edhe kjo nga Komisioni për Ballkanin i Akademisë së Shkencave të Austrisë. Fotografitë e këtyre albanologëve të shquar ndodhen në pjesën e dytë të këtij vëllimi. Udhëtarë të tjerë në jug të Ballkanit bënë fotografi, por pa menduar që do të vinte një ditë kur fotografitë e tyre do të kishin një vlerë të jashtëzakonshme historike kulturore. I tillë ishte rasti i oficerëve holandezë të dërguar në Shqipëri në vitet 1913-1914 për të themeluar xhandarmërinë e parë të Shtetit të sapokrijuar shqiptar. Atyre iu dhanë jo vetëm pajisje të zakonshme ushtarake, por - për fatin tonë të mirë - edhe nga një aparat fotografik. Ata fotografuan gjërat që i panë dhe i përjetuan në një kohë përcaktuese të historisë shqiptare: pavarësia e vonuar e kombit pas pesë shekujve të sundimit osman, ardhja e një mbreti të ri gjerman, Prince Vilhelm cu Vid, për qeverisjen e vendit të vogël ballkanik, dhe rënia e vendit në kaos të shkaktuar nga trazirat e brendshme dhe nga Luftërat Ballkanike në prag të Luftës së Parë Botërore. Shumë fotografi të oficerëve holandezë janë ruajtur deri sot dhe po paraqiten në këtë botim për herë të parë. Autori i këtij vëllimi dëshiron tu shprehë mirënjohjen e tij institucioneve që ruajnë fotografitë e mirëfillta dhe kopjet për bashkëpunimin e tyre. Arkivi Fotografik i Bibliotekës Ndërkombëtare të Austrisë në Vjenë (Bildarchiv, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien) ruan koleksionin e Sekelit me numrin VUES IV 41.055-41.104, koleksionin e Lambercit me numrat Pk 4948, Pk 4950 dhe Pk 4951, dhe fotot e Bajazid Elmaz Dodës me numrat NB902060B deri NB902076B. Koleksioni i Nopçës, nga ana e tij, ruhet në Muzeumin e Historisë Natyrore Kombëtare të Hungarisë (Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum) në Budapesht. Shumica e materialit fotografik të oficerëve holandezë u zbulua në Institutin Holandez të Historisë Ushtarake (Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie) në Hagë. Shpreh mirënjohjen time edhe ndaj personave të mëposhtëm për ndihmën e tyre: Durim Bani në Hagë, Jolien Berendsen- Prins, kryetarja e Fondacionit Thomson në Groningen, Kastriot Dervishi në Tiranë, Okke Groot, arkivisti i Institutit Holandez i Historisë Ushtarake në Hagë, Matthias Hofmann në Halle të Gjermanisë, Gerda Mulder e Muzeumit Fotografik të Holandës (Nederlands Fotomuseum) në Rotterdam, Harrie Teunissen në Leiden, dhe Richard van den Brink në Utrecht. Robert Elsie Hagë, Holandë verë 2007

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |