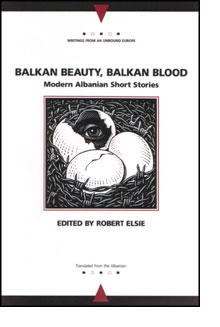

BALKAN BEAUTY, BALKAN BLOOD

Modern Albanian short stories

Edited by Robert Elsie. Translated from the Albanian Writings from an Unbound Europe ISBN 0-8101-2337-1 Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois, 2006 ix + 143 pp. INTRODUCTION The first book in Albanian was written in the year 1555, yet creative prose in that language is very much a twentieth-century phenomenon. Albania was ruled for five centuries by the Ottoman Empire, which banned Albanian-language schooling, Albanian-language writing and Albanian-language publishing. It was only in 1912, when the little Balkan nation finally received independence, that Albanian began to be used in all walks of life, including publishing and creative writing, on more than just a sporadic basis. The earliest serious collections of Albanian prose date from the 1930s with the works of Ernest Koliqi (1903-1975), Mitrush Kuteli (1907-1967) and Migjeni (1911-1938). Indeed the years 1933 to 1944 mark a golden age for writing in Albanian, fleeting as it was. This promising decade was brought to a swift demise at the end of the Second World War when communist partisans took power and set up a primitive Stalinist regime in Albania which lasted unbridled and unimpeded to 1990. The existing intellectual community was terrorized into submission from the very start. Most writers either fled abroad, were executed or were sentenced to long terms in prisons and concentration camps. Albanian literature, indeed Albanian culture, had been silenced. Despite the atmosphere of fear and intimidation which reigned in Albania for almost half a century, the new system made great strides in providing basic education and services for the population and in creating stimuli for a new generation of proletarian writers. The vast body of writing which was churned out in the fifties and early sixties proved, nonetheless, to be sterile and highly conformist in every sense. The subject matter of the period was repetitious, and simplistic texts were constantly spoon-fed to readers without much attention to basic elements of style. It is no wonder that many works of socialist realism remained in the bookstores gathering dust. Political education and fueling the patriotic sentiments of the masses were considered more important than aesthetic values. Even the formal criteria of criticism, such as variety and richness in lexicon and textual structure, were demoted to give priority to patriotism and the politburo's message. The approach taken was designed to reinforce revolutionary fervor and to consolidate the socialist convictions of the new man. Whether it attained its objective to any extent is doubtful. It was insufficient, at any rate, to stimulate talent and to ensure literary quality and thus, in the long run, it did not succeed in satisfying the aesthetic needs of the Albanian reader. The second generation of postwar Albanian writers increasingly came to realize that political convictions, though important within the context of the Albanian society of the period, were not the only criterion of literary merit and that Albanian literature was in need of renewal. The road to renewal was facilitated by a certain degree of political stability and self- confidence within the Albanian Party of Labor despite worsening relations between Enver Hoxha and the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. One turning point in the evolution of Albanian prose and verse, after a quarter of a century of standstill, came in the stormy year of 1961 which, on the one hand, marked the definitive political break with the Soviet Union and thus with Soviet literary models and, on the other hand, witnessed the publication of a number of trendsetting volumes, in particular of poetry: Shekulli im (My Century) by Ismail Kadare, Hapat e mija në asfalt (My Steps on the Pavement) by Dritëro Agolli, and in the following year Shtigje poetike (Poetic Paths) by Fatos Arapi. It is ironic to note that while Albania had severed it ties with the Soviet Union ostensibly to save socialism, leading Albanian writers, educated in the Eastern bloc, took advantage of the rupture to try to part not only with Soviet prototypes but also with socialist realism itself. The attempt made to broaden the literary horizon in search of something new inevitably led to a literary and of course political controversy at a meeting of the Albanian Union of Writers and Artists on 11 July 1961. The debate, conducted not only by writers but also by leading party and government figures, was published in the literary journal Drita (The Light) and received wide public attention in the wake of the Fourth Party Congress of that year. It pitted writers of the older generation such as Andrea Varfi (1914-1992), Luan Qafëzezi (1922-1995) and Mark Gurakuqi (1922-1977), who voiced their support for fixed standards and the solid traditions of Albanian literature and who opposed new elements such as free verse as un- Albanian, against a new generation led by Ismail Kadare (b. 1936), Dritëro Agolli (b. 1931) and Fatos Arapi (b. 1930), who were cautiously in favor of a literary renewal and a broadening of the stylistic and thematic horizon. This march along the road to renewal was finally given the green light by Enver Hoxha himself who saw that the situation was untenable and declared that the young, innovative writers seemed to brandish the better arguments. Though it constituted no radical change and certainly no liberalization or political thaw in the Soviet sense, 1961 set the stage for a few years of serenity and, in the longer perspective, for a quarter of a century of trial and error, which led to greater sophistication in Albanian literature. Topics and techniques were diversified and somewhat more attention was paid to formal literary criteria and to the question of individuality. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, literary prose had thus recovered to an extent and was making good progress, though firmly within the framework of the official doctrine of socialist realism. Many of the most successful prose writers of the late twentieth century have their origins in these years of cautious experimentation: Dritëro Agolli, Teodor Laço and Ismail Kadare. Ismail Kadare is the only Albanian author to have been widely translated and to enjoy an international reputation. His talents both in poetry and in prose lost none of their innovative power over the last four decades of the twentieth century. Kadare's courage in attacking literary mediocrity within the communist system, and later - though subtly - in attacking the political system itself, brought a breath of fresh air to Albanian culture. His works were extremely influential throughout the seventies and eighties and, for many readers, he was the only ray of hope in the chilly, dismal prison that was communist Albania. Much to the regret of the editor, Mr Kadare chose at the last moment not to authorize publication of the three tales of his which had originally been foreseen for inclusion in this anthology with those of the other authors. When the "Socialist People's Republic of Albania" finally imploded in 1990, what remained was chaos - a sub-Saharan economy and little direction or leadership on the part of writers and intellectuals. Half a century of isolation from the rest of Europe had taken its toll. Though a reasonably broad range of Western prose had been published in Kosova, only leftist writers and classic foreign authors of centuries past had been available in Albania itself. Contemporary prose from other European countries or the Americas was unknown. There was now much to catch up on, and readers understandably turned away from their own writers to prefer new, albeit often shabby Albanian translations of the contemporary foreign literature of which they had been deprived for so long. The early 1990s were years of disorientation for Albanian writers themselves because they had no tradition upon which they could build. Initially they imitated the styles and themes of Italian, English, American and French prose, and it is only in recent years that a fresh and unfettered Albanian literature has emerged and crystallized. It is as yet difficult to generalize about the characteristics and concerns of contemporary Albanian prose, but much of it naturally reflects the Albanian experience, bitter as it has been over the last few decades and up to the present. After a brief and mostly unsuccessful attempt to come to terms with the horrors of the past, writers are turning increasingly to reflections on the very diverse aspects of contemporary life in Albania and Kosova, and in particular on themes of Albanian emigration. Albanian literature - especially modern Albanian prose - remains little known in the outside world. This is due primarily to the glaring lack of literary translators from Albanian into English and other foreign languages, but also to the traditional isolation from which Albania and its people have suffered. Two hundred years ago, historian Edward Gibbon described Albania as "a land within sight of Italy and less known than the interior of America." At the cultural and literary level at least, little has changed. The present collection of Albanian short stories and prose extracts is but an introduction and is not intended to mirror the full range of Albanian prose. It nonetheless endeavors to reflect the best of modern writing from the last three decades, in particular the 1990s. Included are prominent and well-established authors from Albania and from the large Albanian communities of Kosova and Macedonia, as well as some new-comers to the literary scene. After decades of muteness, Albanian writers have many tales to tell. It remains for me to thank all the authors in question for their kind co-operation. Particular thanks also go to Janice Mathie-Heck of Calgary, Canada, for her vital assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editor's Introduction Stars Don't Dress Up Like That Elvira Dones The Men's Counsel Room Kim Mehmeti The Loser Fatos Kongoli The Slogans in Stone Ylljet Aliçka Adonis Ylljet Aliçka The Couple Ylljet Aliçka Ferit the Cow Fatos Lubonja An American Dream Stefan Çapaliku The Mute Maiden Lindita Arapi The Snail's March Towards the Light of the Sun Eqrem Basha The Secret of my Youth Mimoza Ahmeti The Pain of a Distant Winter Teodor Laço Another Winter Teodor Laço The Appassionata Dritëro Agolli About the authors

| Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact |